By Thornton May

Futurist, Senior Advisor with GP, Executive Director & Dean - IT Leadership Academy

If you are working in IT today what will you be doing ten years from now? For some, the happy answer to this question will be “Nothing. I will be retired.” For twenty two of the twenty seven years that Gary Beach, author of The U.S. Technology Skills Gap: What Every Technology Executive Must Know to Save America’s Future worked at IDG [publisher of Computerworld, Network World and CIO Magazine] the median age of an IT worker was 42. Today the median age of an IT worker is 51.This blog post is not for those of you who will be retired in the next ten years. For those of you who will still be working, I have been examining what IT work will look like in the future.

Thinking about the future of work is not and never has been the sole purview of futurists. No less an economist than John Maynard Keynes took a stab at this in 1931 when he wrote a short essay, Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren. The essay contains:

[1] a remarkably modern account of the determinants of economic growth, [2] a set of predictions concerning living standards and working habits one hundred years on [i.e., in 2030], and [3] some speculations about people’s future lifestyles, based on his moral philosophy and aesthetical views.

…he predicted that, by 2030, the grandchildren of his generation would live in a state of abundance, where satiation would be reached and people, finally liberated from such economic activities as saving, capital accumulation, and work would be free to devote themselves to arts, leisure, and poetry.*

The freedom from want, a fifteen hour work week and abundance of leisure time Keynes predicted would be made possible by technology advancement. Specifically automation – machines replacing human labor. What Keynes did not address head on in his essay was the issue of technological unemployment. This means unemployment due to our discovery of means of economizing the use of labor outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labor.

In The End of Work Jeremy Rifkin, has argued that, with the computer revolution taking over businesses, fewer jobs will be required in the economy. A report by Oxford researchers finds that 45% of America’s occupations will be automated within the next 20 years. Steven Rattner in a New York Times piece “Fear Not the Coming of the Robots” [21 June 2014] puts a contemporary spin on Keynes’ prediction of the impact of technology on work and workers:

Throughout history, aspiring Cassandras have regularly proclaimed that new waves of technological innovation would render huge numbers of workers idle, leading to all manner of economic, social and political disruption.

As early as 1589, Queen Elizabeth I refused a patent on a knitting machine for fear it would put “my poor subjects” out of work.

Consider the case of agriculture, after the arrival of tractors, combines and scientific farming methods. A century ago, about 30 percent of Americans labored on farms; today, the United States is the world’s biggest exporter of agricultural products, even though the sector employs just 2 percent of Americans.

Wags in San Francisco predict that drone rescue will become one of the major jobs of IT professionals. Some observers of the macro IT work environment predict that what happened to American farm labor will happen to American IT labor. It will disappear.

What do you think?

* Lorenzo Pecchi and Gustavo Piga, Revisiting Keynes Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren [Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008].

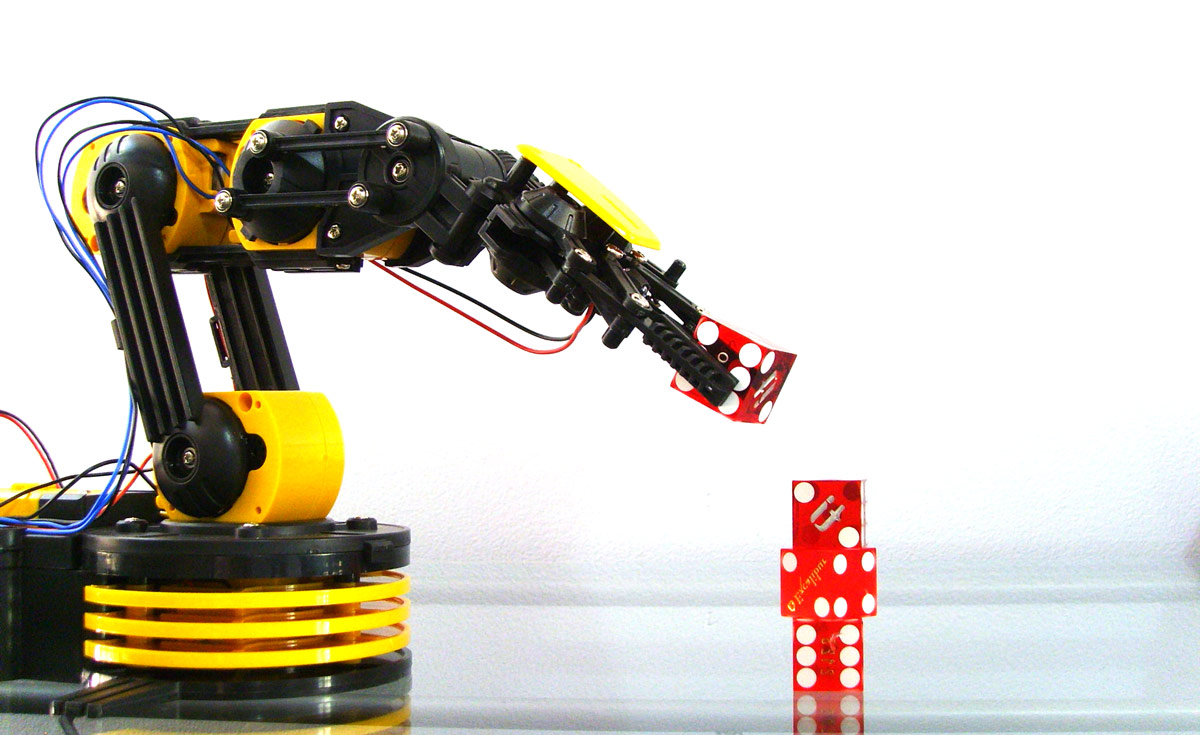

* Photo by Dan Ruscoe via Flickr

42 Berkeley Square

London W1J 5AW, UK

Phone: 44(0)20.7318.0860

Fax: 44(0)20.7318.0862

info@gustinpartners.com